Questions or comments? Please email me at:

My first and only encounter with papier-mâché was in 4th grade art class at Stafford Elementary School. I don’t recall what I constructed out of that messy mixture of milky glue, newspaper and gauze, but I am certain of two things. First, like Van Gogh, my artistic aptitude was unappreciated in my heyday. Second, there is no way that thing survived the gauntlet of an elementary school hallway, a 4th grader’s backpack, and a ride home on Bus 69.

Given my expertise in this elementary school art form, I've always found it strange that in 1903 the Intercollegiate Football Association banned the use of papier-mâché and other “hard or unyielding material” in football head protectors. It’s difficult to imagine a football player seeking the protection of a helmet made out of paper or said helmet being such a danger to other players that the Association had to prohibit its use.

Given my expertise in this elementary school art form, I've always found it strange that in 1903 the Intercollegiate Football Association banned the use of papier-mâché and other “hard or unyielding material” in football head protectors. It’s difficult to imagine a football player seeking the protection of a helmet made out of paper or said helmet being such a danger to other players that the Association had to prohibit its use.

Paper Football Helmets?

Chris Hornung

January 15, 2017

Delving into this historical anomaly wasn’t much of a priority until I received an email in September from Bill Bussone, a researcher working on the history of helmet engineering and biomechanics. Bill was curious whether or not there was any documentation on the existence of papier-mâché football helmets. After a healthy email dialogue questioning the practicality of a paper helmet, Bill recommended I look into “pulp ware” a late nineteenth century British invention that utilized a similar manufacturing process as papier-mâché.

In 1878, Edward Charles Vickers and Edwin William Knowles were awarded an English patent for improvement in the treatment and application of vegetable and animal pulps or fibres for the manufacture of hollow and molded articles in imitation of leather, earthenware or papier-mâché. Vickers and Knowles patent process produced a product referred to as "pulp ware," which was similar to papier-mâché but waterproof as a result of soaking the pulp in linseed oil and applying finishing coats of lacquer. According to Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History, pulp ware was manufactured as follows:

Pulp Ware

The material was first cleaned by boiling with lime, then shredded in rag engines for two days to form a slurry with water. Most of the water was extracted by feeding the pulp into sieve-like formers roughly the shape of the final object. Additional water was removed with a vacuum pump and finally an hydraulic press squeezed out the remaining moisture. These blanks were placed in a drying shed for one to four weeks. When dried they felt very much like cardboard, and were stamped or embossed into their final shape by powerful cam operated machines. They were then soaked in linseed oil to make them water repellent, which turned them from grey to brown and then the decoration was added using several long and varied processes. Printed paper transfers were used for decoration or for applied advertising, and a top coat of japan or lacquer was added to make them water and acid proof.

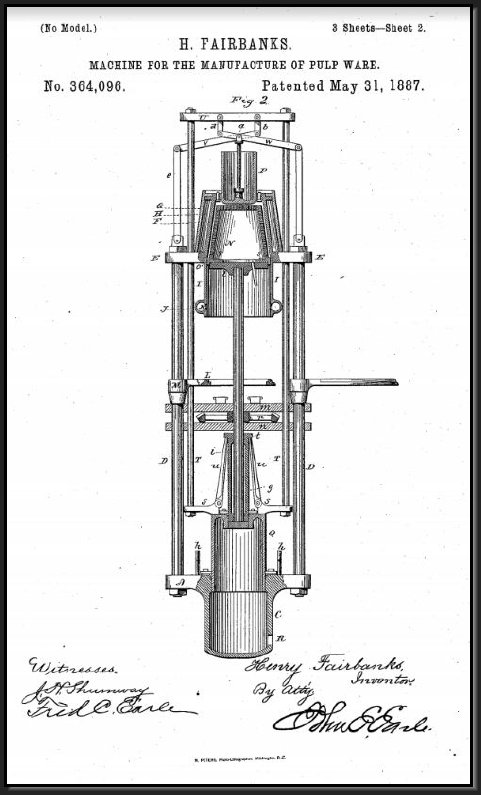

In 1887, Henry Fairbanks of St. Johnsbury, Vermont, patented an improved “Machine for the Manufacture of Pulp Ware.” Fairbanks’ patent illustrations show the type of industrial equipment used to exert pressure to liquid pulp to press it into a variety of "hollow ware" products, such as buckets, pails, and vases. By the late 1890's, pulp was used in the manufacture of furniture, pipe, telegraph poles, boats, automobile wheels, bicycle frames, coffins, and even artificial teeth. The manufacturing process would continue to be popular in the United States until the late 1950's when it was replaced by polyethylene and other plastics.

American Production

The Manufacturer and Inventor, June 20, 1891

Pulp ware proved to be such a lightweight, yet durable material, that it was referred to as "Unbreakable Steel Pulp Ware" by W.B. Fordham & Sons, the sole selling agent for the United Kingdom. The material was used to manufacture pots, vases, bowls, trays, toilet covers, life preservers and capital helmets for a fraction of the cost of steel or ceramics. A December 5, 1888 article in "Colonies and India" told a story of a pulp ware salesman who demonstrated the strength of his product by throwing toilet basins high into the air and then jumping upon them to no effect once they landed upon the ground.

“Patent Pulp Manufacturing Co.” Graces Guide, n.d. Web. 28 Dec. 2016.

There's no record of any sporting goods manufacturer producing a papier-mâché or pulp ware football helmet, and no known surviving examples. However, there are several examples of pulp ware helmets for other purposes from the same timeframe, including mining, military, and fireman helmets. The fact that the Intercollegiate Football Association chose to ban "papier mache, or other hard or unyielding material" from football head gear is evidence that they may have been produced or at least proposed for use in football games.

If one did exist, what would a pulp ware football helmet look like? For starters, pulp ware could be decorated as imitation leather, so it may be more difficult to discern than one may think. Based on the manufacturing process, it would probably look similar to an improved head harness with a hard, rigid, one-piece crown onto which leather or canvas ear flaps would have been riveted or tied. Keep an eye out for what could be the lone surviving example of the elusive paper football helmet.

If one did exist, what would a pulp ware football helmet look like? For starters, pulp ware could be decorated as imitation leather, so it may be more difficult to discern than one may think. Based on the manufacturing process, it would probably look similar to an improved head harness with a hard, rigid, one-piece crown onto which leather or canvas ear flaps would have been riveted or tied. Keep an eye out for what could be the lone surviving example of the elusive paper football helmet.

Pulp Ware Football Helmets?

Early 1900's miner's helmet, www.norfolkmills.co.uk

WWII tank helmet, www.norfolkmills.co.uk

Spalding No. 50 Improved Head Harness, photo courtesy of Steve Hill

References

Neville, Jonathan. "Norfolk Mills - Thetford Paper Mill." Norfolk Mills., 2003. Web. 01 Jan. 2017.

Patent Illustration, H. Fairbanks, May 31, 1887